Alright, here it is: The Fault in Our Stars is not only a very moving novel in which readers laugh, cry, and keep asking for more, but it’s also a narrative in which the characters actively confront and speak against traditional “disability tropes.” I’m completely aware that there has been (and still is) somewhat of a contentious relationship with the categories and experiences of “illness”/”disease” in relation to the category/identity of “disability.” Let’s just say that I know that… and I’m planning to leave that debate at the front door. While that discussion is hugely rich and can tease out a great number of nuanced experiences, I’m arguing for a *reading* of disability (i.e. reading through a disability “lens” or “framework”) of The Fault in Our Stars, both because I think such a reading will be hugely productive and because the characters themselves use words like “disability” to describe their experiences, so why not let them claim it?

Let me just say here that this book contains some great moments when the characters (particularly Hazel, Augustus, and Isaac) speak back to and/or are active agents in creating their own “disabled experience.” Here are a few of the (arguably) most poignant examples:

First, let’s start with Isaac, a faithful friend of both Augustus Waters and Hazel Grace. After the surgery that results in his blindness, he wryly tells Hazel, “people keep saying my other senses will improve to compensate, but CLEARLY NOT YET… Come over here so I can examine your face with my hands and see deeper into your soul than a sighted person ever could” (74). In not-so-many words, Isaac is critiquing the figure of the disabled “super-crip”—a person with a disability who has so far overcome their disability that they’ve surpassed both temporarily-able-bodied and disabled folks by developing something “extra special.” This is an unfortunate and problematic figure, because many people with disabilities do not, in fact, develop “extraordinary” abilities and are simply people.with.disabilities. full stop.

My second favorite comes from good ol’ Gus who is so moved by the injustice of the persecution of the innocent at the Anne Frank House that he tells Hazel they should “team up and be this disabled vigilante duo roaring through the world, righting wrongs, defending the weak, protecting the endangered” (202). She indulges his fantasy, quipping,” our fearlessness shall be our secret weapon” (202). Again, though Hazel and Augustus don’t articulate it as such, they’re calling upon time-honored tropes of “disability as super-power” (think, for example of Professor X, Batgirl, Daredevil, the Hulk, etc.) and turning it on its head by continuing, “ when the robots [of the future] recall the human absurdities of sacrifice and compassion, they will remember us” (202).

We’ve now gotten to my third, and final, critical disability example: The parallel between An Imperial Affliction and The Fault in Our Stars. Sidenote: what is with Hazel’s borderline-obsession with An Imperial Affliction (AIA) anyway? Is it a metaphor or parallel for all of the little obsessions of nondisabled American teenage girls? I don’t think so. Partly because Hazel does have a number of average-teenage-girl interests: she goes to the mall with her best gal friend, watches America’s Next Top Model religiously, fights with her parents, and enjoys sleeping in in the mornings. No, Hazel is infatuated with AIA for another reason altogether. Hazel explains that Peter Van Houten seems to “understand [her] in weird and impossible ways” (34), articulating the experience of a young person experiencing illness in a way completely antithetical to the traditional tropes of “disability as metaphor,” “disability as tragedy,” “disability as charity-case,” or “disability as overcoming/inspiring.” Indeed, Anna, the protagonist of AIA, is so hyper-aware of her of these tropes that she “decides that being a person with cancer who starts a cancer charity is a bit narcissistic, so she starts a charity called The Anna Foundation for People with Cancer Who Want to Cure Cholera” (49). Brilliant. This girl sounds like a bad-ass and a smart-ass. It’s no wonder Hazel finds such affinity in with her. Let’s pause here and think about this for a minute: A “cancer book” where the main character doesn’t start a charity, “overcome” some insurmountable obstacle to be an “inspiration” to others, and who’s illness isn’t portrayed as a “tragic” event; instead, simply a part of one’s life experience and a variation of human existence? Sounds a lot like The Fault in Our Stars, am I right? Very meta, John Green, very meta indeed. Which brings me to the actual point of this blog post (sorry, I know, if you’re still reading this you’re probably thinking: it’s about damn time!), but seriously if all of these breadcrumbs are sprinkled throughout the text for readers to follow and eventually wind up thinking at the end: well that was a moving story in which people did interesting and meaningful things, then why did the Hollywood-ization of the story erase these moments of “talking back?”

I’m not a conspiracy theorist (I don’t think?) but I do think that Hollywood has a very specific idea about what sells, which in turn creates very specific ideas in the minds of the generally able-bodied public about “the real” experience of disability. Why might the lines about Hazel and Augustus being disabled vigilantes be left out? Yes, it cleans up the dialogue a bit, but it also makes their portrayal as star-crossed teenage lovers more direct. If they aren’t articulating agency in their roles as cancer patient/amputee, then their passive acceptance of the tragically fated love is all the more palatable to audiences. If Isaac doesn’t make a snarky comment about his other senses making up for his blindness, then his character is much more easily read as a sympathetic one that requires the sympathy and charity of Augustus and Hazel.

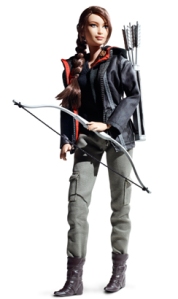

This isn’t the first time a Hollywood rendition of a novel has erased some of the most critical representation and articulation of disability (for another example, see Disability: Lost in the Translation of the Hunger Games), but it is a particularly unfortunate erasure because the very nature of the novel itself. Much like the nature of An Imperial Affliction that Hazel idolizes so much is wrapped up with the critical reflection of the main characters. By skipping these moments of critique and hyper-awareness of the ways in which disability is often represented in popular culture, Hollywood is not doing the general public (disabled and non-disabled alike) any favors.

Green, J. (2012). The Fault in Our Stars. New York, NY: Penguin Books.